10 AI Agents, 4 Hours, $30: A Field Report on OpenClaw

How we had a team of 10 autonomous AI agents build an invoicing application — and what it changes for the future of software development

The starting point

“Vibe coding”, the practice of coding in free-form dialogue with an LLM, has obvious limitations. It works well for a script, an isolated component, or a quick prototype. But as soon as a project moves beyond the POC stage, the lack of structure becomes costly: loss of context, architectural inconsistencies, recurring bugs, and zero traceability.

What if, instead of interacting with a single model, we had an entire team of specialized agents collaborate, each with its own role, memory, and responsibilities?

That’s the hypothesis we tested at Castelis by combining two open-source building blocks: OpenClaw for multi-agent orchestration, and prompts from the BMAD methodology to define our agents’ roles.

The tools: OpenClaw and BMAD in a nutshell

What is OpenClaw?

OpenClaw is a self-hosted, open-source AI agent runtime. Concretely, it’s a persistent Node.js service that runs on your server and exposes your agents via Telegram, WhatsApp, Discord, or web chat.

Each agent has its own workspace (personality files, memory, tools), persistent sessions, and can communicate with other agents through an inter-agent messaging mechanism (sessions_send).

BMAD (Breakthrough Method of Agile AI-Driven Development)

BMAD is a framework that defines agent roles modeled after a real agile team: analyst, product manager, architect, UX designer, developer, QA, scrum master, and ops.

Each role is described in a Markdown file that serves both as a persona definition and as operational instructions.

Our hybrid approach

We did not use BMAD directly as a framework. Instead, we extracted its agent prompts and injected them into the SOUL.md files of our OpenClaw agents.

For example, the BMAD Analyst prompt became the foundation of the SOUL.md for our OpenClaw agent Mary (analyst). This allowed us to benefit from BMAD’s methodological rigor while leveraging OpenClaw’s persistence and inter-agent communication.

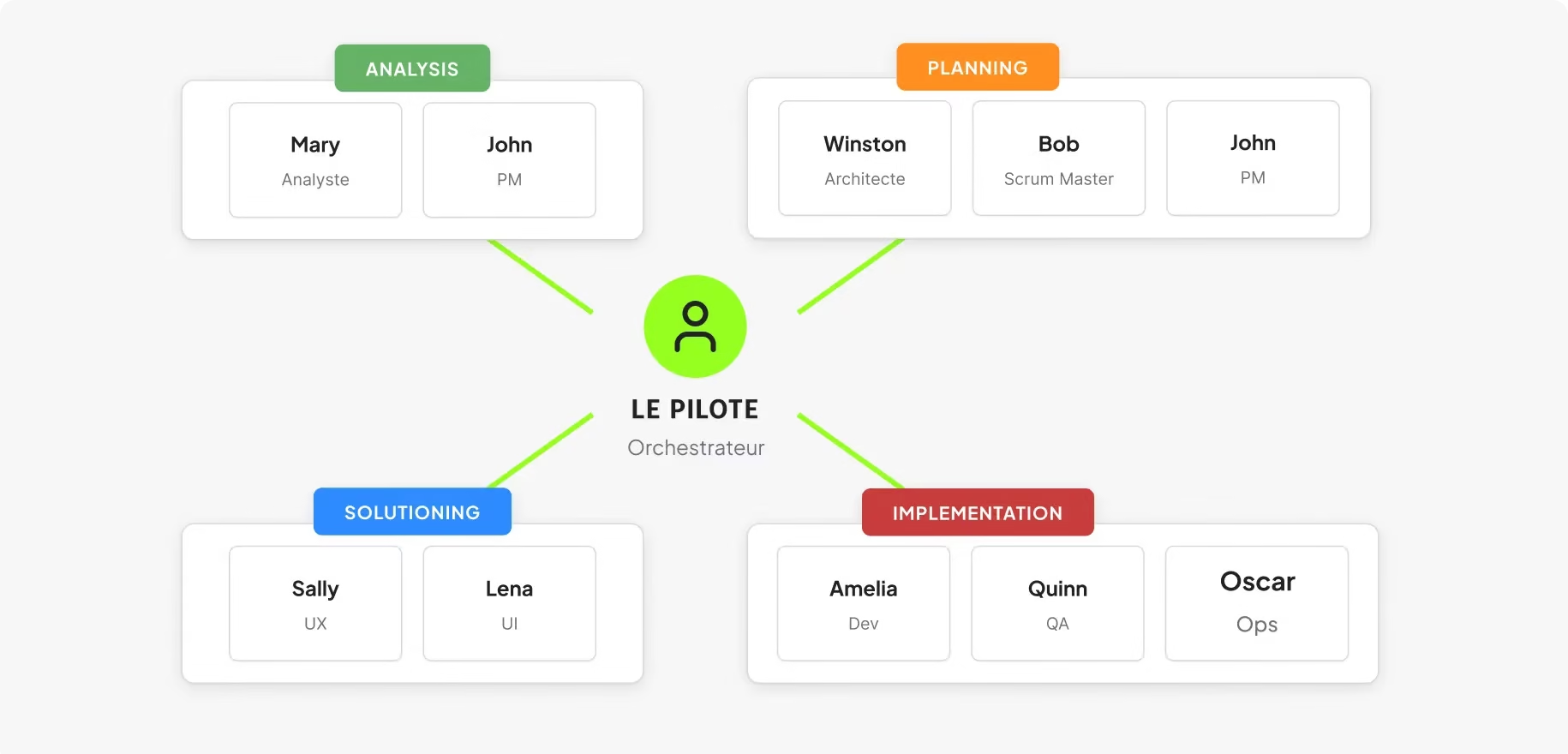

The architecture: 10 agents, one orchestrator, zero vibe coding

We deployed 10 agents on a minimal Debian server (2 vCPU, 2 GB RAM) with Nginx as a reverse proxy and Let’s Encrypt for SSL. Infrastructure cost: close to zero.

Each agent has a clear identity, a precise role, and persistent memory:

-

The Pilot (orchestrator) assigns tasks, tracks progress, and maintains the global project context. It doesn’t code or design, it coordinates.

-

Mary (analyst) produces business briefs.

-

John (PM) writes PRDs, epics, and stories.

-

Winston (architect) defines the technical architecture and ADRs.

-

Sally (UX) and Lena (UI) handle user experience specifications and visual identity respectively.

-

Bob (scrum master) manages sprint planning.

-

Amelia (dev) implements the code and pushes to GitHub via a configured SSH key.

-

Quinn (QA) tests and validates.

-

Oscar (ops) handles deployment and server security.

The entire system follows the BMAD pipeline across four phases: Analysis, Planning, Solutioning, Implementation.

Each agent receives tasks with a standardized context block (project, slug, path, current phase), and all produced artifacts are stored in a shared file structure through project-context.md.

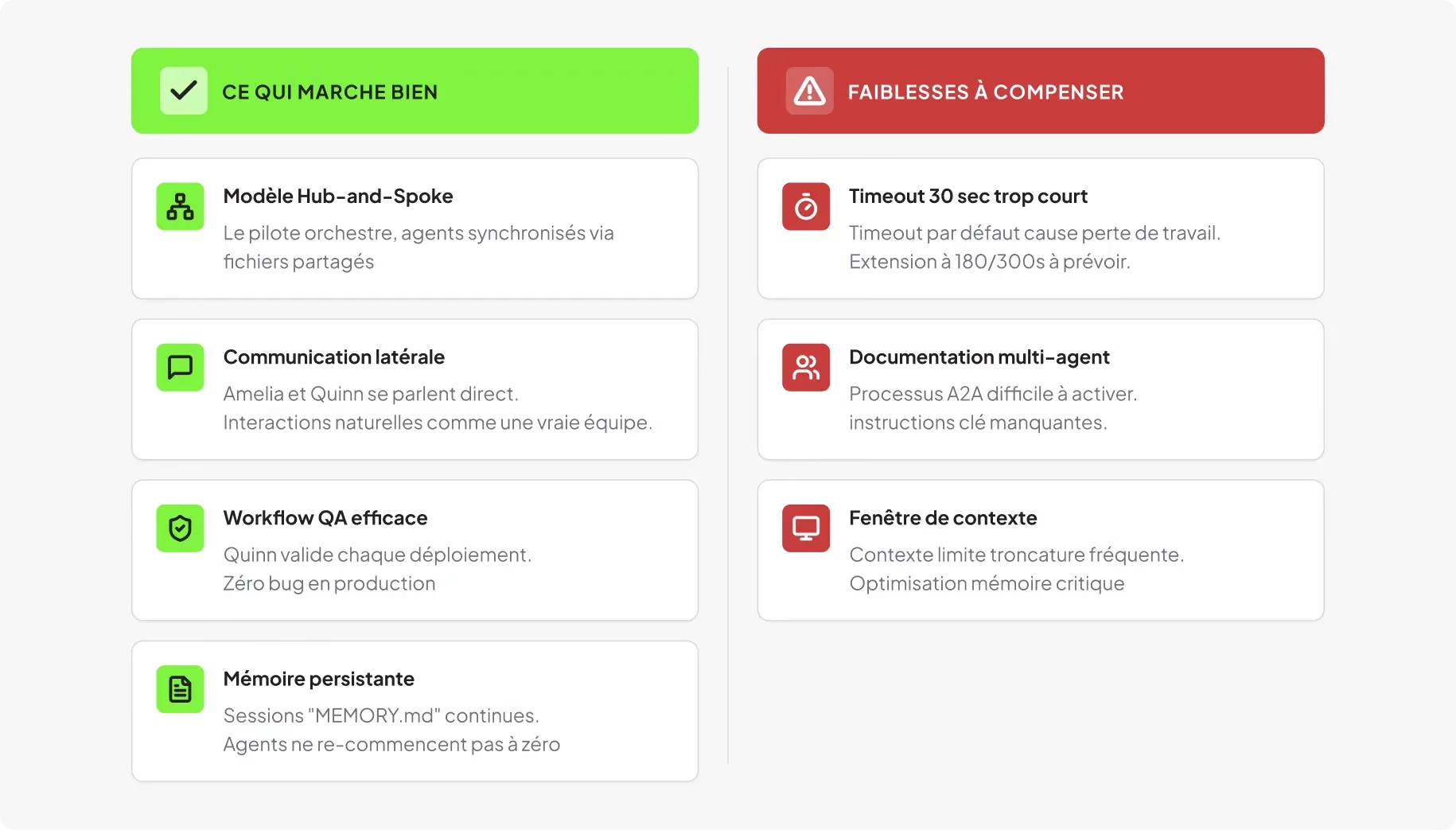

What worked

The hub-and-spoke model holds up

The Pilot orchestrates, agents execute, and context flows correctly between agents through shared files. Agents stay within their roles and produce artifacts in the right place.

Lateral communication feels natural

Allowing agents to communicate directly, (for example: Amelia notifying Quinn that a release is ready or Quinn reporting a bug directly back to Amelia) reproduces real team dynamics.

The safeguard “no re-delegation” (an agent cannot delegate to a third party) prevents uncontrolled chains of delegation.

The QA workflow proved its value from day one

Simple rule: no deployment without Quinn’s validation.

As soon as this rule was enforced, production bugs dropped to zero. The QA agent caught issues the dev agent had missed, exactly as in a human team.

Persistent memory changes everything

Each agent has its own MEMORY.md and access to shared context files. Between sessions, an agent resumes exactly where it left off.

This is what differentiates this setup from simple prompt engineering: we move from ephemeral conversations to continuous collaboration.

The pitfalls: what the documentation doesn’t tell you

The 30-second timeout is a silent killer

This was the most insidious issue we encountered.

The default timeout for sessions_send in OpenClaw is 30 seconds. Our agents regularly take longer than that to produce documents (briefs, PRDs, implementations).

When the timeout expires, the result is never saved in the session history. OpenClaw injects a synthetic error result, and the agent loses all the work it just produced. No visible error on the user side.

The fix: explicitly set timeoutSeconds , minimum 180 seconds for standard tasks, 300 seconds for longer documents.

Multi-agent documentation is incomplete

We had to read OpenClaw’s source code to understand that:

-

tools.agentToAgentmust be explicitly enabled (disabled by default), -

both agents (source and target) must be listed in an allowlist,

-

and the distinction between

sessions_send(A2A messaging with persona and memory) andsessions_spawn(ephemeral sub-agent without context) is critical.

We use sessions_send exclusively.

Context window management remains critical

Workspace file size limits injected into the context cause silent truncations. The Pilot’s MEMORY.md, at 9,000 characters, exceeds the limit and gets truncated.

More fundamentally, agents eventually “forget” decisions made in previous sprints, leading to recurring bugs — typically deployment errors or regressions on previously validated architectural choices.

This is the single most critical optimization point for maintaining long-term project consistency.

The numbers

The first project, an invoicing application for small businesses and freelancers (Express.js + PostgreSQL backend, React + Vite frontend), was developed in roughly 4 hours of LLM usage for a total cost of $30.

The default model was Claude Haiku 4.5 for cost-efficiency, with occasional calls to Claude Opus 4.5 for complex tasks.

Nine stories were implemented in the first sprint: customer CRUD, invoice CRUD, PDF generation, and status management.

Let’s be clear: the result is a functional POC demonstrating feasibility, not a production-ready product.

However, the cost-to-output ratio is remarkable and opens concrete opportunities for real-world projects.

Our recommendations going forward

Adapt the number of agents to the context

Ten agents are probably too many for most projects. Merging UX and UI, PM and Scrum Master, or combining roles depending on the phase, would reduce coordination overhead without sacrificing quality.

The ideal setup is not static. It should evolve with the project phase (initial development, debugging, feature expansion).

Define phase-specific workflows

The linear Analysis → Planning → Solutioning → Implementation pipeline works well for initial development.

For debugging or feature additions, a lighter workflow with fewer agents and shorter feedback loops would be more efficient.

Treat agent documentation like code

Any change to AGENTS.md, TOOLS.md, or SOUL.md alters agent behavior.

It should be versioned in Git, reviewed, and deployed with the same rigor as application code.

Invest in memory management

Break memory files into smaller chunks, implement periodic summarization mechanisms, and actively monitor context truncation.

This is the key to moving from POC to real project usage.

Next steps: observability and scaling up

Two improvement axes clearly emerge to move from POC to industrial-grade usage.

Add an LLM observability layer

Today, our visibility into agent behavior is limited to OpenClaw gateway logs (14 MB per day of activity) and manual inspection of generated artifacts. That’s insufficient at scale.

At Castelis, we already use Langfuse in production for LangChain-based AI projects. It’s an open-source, self-hostable LLM observability platform that traces every LLM call (prompts, responses, token usage, latency), tracks costs in real time, and detects anomalies.

The natural next step is to extend this instrumentation to our OpenClaw multi-agent setup: trace inter-agent exchanges, measure consumption per agent and per project phase, identify looping agents or quality degradation.

In a system with 10 autonomous agents, this visibility isn’t optional, it’s a requirement for viability. Without it, you’re flying blind.

Both communities are actively exploring OpenClaw/Langfuse integration via OpenTelemetry, and a Langfuse maintainer is ready to release an official integration.

The convergence between multi-agent orchestration and LLM observability is no longer a matter of if, but when.

Test more robust models than Haiku

Our POC relied primarily on Claude Haiku 4.5, chosen for its cost-performance ratio. It’s well-suited for repetitive, well-scoped tasks (CRUD operations, formatting, deployment).

But for high-complexity tasks, architecture analysis, subtle bug resolution, design decisions — its limits become apparent.

Recurring deployment errors were partly due to the model’s reasoning limitations on multi-step problems.

The next step is to test a more granular routing strategy: lightweight models for execution tasks, more powerful models (Claude Sonnet 4.5 or Opus 4.6) for reasoning-heavy tasks.

The additional API cost would likely be offset by reduced time spent fixing avoidable errors.

What this signals for the software development lifecycle

This experiment goes beyond a technical exercise. It illustrates a deeper evolution of the SDLC: moving from AI as a point-assistance tool (copilot, code completion) to AI as a team of autonomous agents executing an end-to-end engineering pipeline under human supervision.

Multi-agent AI isn’t prompt engineering, it’s systems engineering.

Configuration, timeouts, memory management, inter-agent coordination, these are infrastructure problems, not prompt problems. And that’s precisely what makes the approach viable for organizations that require rigor, traceability, and reproducibility.

For companies, the question is no longer “Can AI write code?” but “How do we structure a team of AI agents to produce reliable, maintainable outcomes?”

At Castelis, we’re continuing to explore that question and the early results are promising.